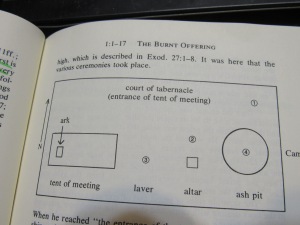

1If his offering is a sacrifice of peace offering, if he brings near cattle from among the herd, a male or female, he will offer it without blemish before the LORD. 2He will lay his hand on the head of his offering and will kill it at the entrance to the tent of appointment, and the sons of Aaron, the priests, will splash the blood all around the altar. 3And from the sacrifice of the peace offering, as an offering made by fire the LORD, he will bring near [offer] the fat covering the entrails and all the fat that is on the entrails, 4and the two kidneys with the fat that is on them at the loins, and the long lobe of liver that he will remove with the kidneys. 5Then the sons of Aaron will send it up in smoke on the altar on the burnt offering that is on the wood that is on the fire; it is an offering made by fire—a soothing aroma to the LORD. 6If his offering for a sacrifice of peace offering to the LORD is from the flock, male or female, he will offer it without blemish. 7If he offers a young ram for his offering, he will offer it before the LORD. 8He will lay his hands on the head of his offering and kill it before the tent of appointment, and the sons of Aaron will splash the blood all around the altar. 9Then from the sacrifice of the peace offering he shall offer as an offering by fire to the LORD its fat, and the whole fat tail that he will cut off from close to the backbone, and the fat that covers the entrails and all the fat that is on the entrails, 10and the two kidneys with the fat that is on them at the loins, and the long lobe of liver that he will remove with the kidneys. 11Then the priest will send it up in smoke on the altar as a food offering to the LORD. 12If his offering is a goat, he will bring it before the LORD. 13And he will lay his hand on its head, and will kill it at the opening of the tent of appointment, and the sons of Aaron will splash the blood all around the altar. 14Then he will offer from it, as a fire offering to the LORD, the fat that is covering the entrails and all the fat that is on the entrails, 15and the two kidneys with the fat that is on them at the loins, and the long lobe of liver that he will remove with the kidneys. 16And the priest will send them up in smoke on the altar as a fire offering with soothing aroma. 17All fat is the LORD’s. It will be a custom forever through your generations in all your dwelling places: you will eat neither fat nor blood.

This third offering is called the שׁלם offering, or the “peace” offering. It is commonly referred to as the “fellowship” offering, since the Hebrew word is associated with fellowship. This sacrifice is part of the ritual that provides reconciliation with God. The burnt offering expiated sin, the cereal offering was about worship, and the peace offering is about being in His presence. Though we may not feel like it, in our natural state we are enemies with God. Paul tells the Romans that before people come to Jesus they are God’s enemies (Ro 5.10), and he tells the Colossians that “you were alienated and hostile in your minds because of your evil actions” (Co 1.21). According to Mosely, there are five facts that form the theological basis of the sacrifice:

- God is holy, and no sin is allowed in His presence.

- God is just, and must therefore punish sin.

- The penalty for sin is death.

- People are sinners, so we’re not allowed in God’s presence, and we are headed toward death.

- God is gracious and loving enough to have provided the means by which we may be reconciled to Him.

It is important to note that this was an offering that could be set up at any time. Often offered on highest occasions in Israel’s history— Covenant at Mount Sinai (Ex 24.5), installation of Saul as King (1 Sa 11.15), David’s bringing of the Ark of the Covenant to Jerusalem (2 Sa 6.17-18) dedication of Solomon’s Temple (1 Ki 8.64). It was yet another acknowledgment that God had provided the means for atonement, just like He had with Abraham on the mountain with Isaac.

The worshiper would lay hands on the head of the animal. This was a symbol of identification with it—a ceremonial association with the animal. It symbolized the transfer of sins from the worshiper to the animal. On the Day of Atonement, the high priest would lay his hands on the sacrificial animal and confess the sins of Israel, transferring their transgressions onto the animal. Each individual worshiper did the same in the peace offering. In doing this, he was actually doing four things: (1) acknowledging guilt; (2) affirming God’s just penalty; (3) acknowledging principle of substitutionary atonement; and (4) seeking God’s atonement.

Some might ask: “why all the detail about the livers and kidneys and stuff?” Great question. In ancient Mesopotamian culture, livers were associated with Mesopotamian divination. Instead of trying to divine the future, the worshiper is trusting God for the future. The kidneys were associated with the seat of emotions, like the heart to English-speakers. Thus, the worshiper is trusting God with his inmost thoughts, emotions and motives. The fat was considered the best part of the animal. If the animal is analogous to man, the worshiper is then offering the best part of himself to God. As with the burnt offering, part of the priest’s job here is to splash the blood all around the sides of the altar before sending it up in smoke as a soothing aroma to God. This symbolized that God was pleased to accept the sacrifice on behalf of the offerer (Hartley).

I think it is important to note here that these sacrifices were never mindless rituals; there was so much detail that the worshiper had to stop and think about what he was doing, and how to obey God’s word. There was a careful diligence involved. Another important difference with respect to the peace offering is that it, unlike the burnt offering, is a meal. Specifically, it was a festive meal eaten in or near the sanctuary (Wenham). The priest was given the breast and right thigh of the animal (7.31), symbolizing that God intended for the priesthood to take its living from the full-time service to His people. Verses 11 and 16 show the worshiper eating. In the New Testament, the Last Supper is the transition ritual, and celebrating the Lord’s Table today is the New Covenant version of this peace offering. We are meant to be in fellowship, and peace and fellowship are symbolized by the breaking of bread. We are simply unable to “walk the Christian walk” outside the community of faith. How would that even be possible, given all the “one anothers” that exist in the New Testament (Ja 5.16, He 10.25, Ga 6.2, He 3.13, Jn 13.34, 1 Pe 4.10, Eph 4.32)?

Application #1: God has reconciled us to Himself through the ultimate sacrifice of His Son, Jesus Christ. It is His will that we be reconciled to one another. While we no longer have to physically lay our hands on an animal to engage in reconciliation (again, this was already done by God), the celebration that we have each time we take the Lord’s Supper is a sort of New Testament ritual that demonstrates this reconciliation. It is a time of peace offering—fellowship with one another, as God intended. I think there is much to be learned in the biblical teaching of eating with one another generally, too….outside of the Lord’s Table, we should regularly break bread with one another. It is the ultimate peace and fellowship symbol.

Application #2: When we come before God each Sunday, do we just stand around mouthing some Chris Tomlin words? Or do we also acknowledge our guilt and His sacrifice that rectified it? Do we come before Him in reverence and submission, or are we doing a chore? The attitude is the difference. We are called to bring a sacrifice of praise.

Application #3: Do we offer our best to Him? Or do we give Him what we have left over at the end of a hectic week? If that’s our attitude, it’s very likely that we don’t even show up in His house at all over time. Tithing is one way to give God your firstfruits—your best—but giving Him the firstfruits of your time is even more valuable. It’s the one resource you never get back, once you’ve spent it. To invest it in His presence with His people is giving Him your best. And what about your gifts and talents? What about your skills? Can you type? Do you know Office software? Do you understand how to run a Power Point presentation? Can you vacuum a carpet? Can you mow grass? Can you watch the nursery? If you’re “giving your best” to a boss that pays you money and maybe kinda-sorta giving God what’s left over at the end of the week, you are doing this wrong.

Application #4: When you come before God, are you diligent? Do you care about how He has taught your worship to be done, or are you only interested in doing it the way you’ve always done it? Do you value and revere His word enough to follow His instructions—even when they conflict with your previously held views?

Application #5: Are you aware that God has always intended for ministers to take their livings from the ministry? From the Aaronic priesthood to the stinginess of the Corinthian church (chapter 9), biblical teaching has always been consistent: the people of God bring their tithes and offerings into His house, and their slave the priest takes his living from it. While the rest of the Israelites were allowed to inherit land and have possessions that God gave them from the Canaanites, the priests were not—their portion was service in God’s house. Are you mindful of this when you make decisions about the money with which God has momentarily blessed you?

These are all valid applications relevant to our modern worship. It is important in His prescriptions on worship that we are diligent in following His instructions. What are those, according to chapter 3? Are we bringing God our best, being faithful to those who serve us in His house, approaching His presence with reverence and gratitude, and breaking bread with one another?